Venture capitalists worldwide make more than $100 billion in investments annually, but rather than making those choices by following a rigorous, analytic process, the average professional looking to finance the next Facebook or Uber relies more on the magic of gut instinct.

That’s not just an informed opinion by a venture capitalist who invests in early-stage companies, but the finding of a recent Harvard Business School paper by Paul Gompers et al titled “How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions?”. Most professionals in other areas of the financial world — from hedge funds to real estate investors — faithfully use financial metrics to calculate their risk-adjusted return, whether that’s an internal rate of return, a multiple on invested capital, or some other measure. However, this type of rigor is not routine in venture capital.

The Harvard study found that among all VCs, 9 percent don’t use any financial metrics to make decisions while 17 percent of early-stage VCs don’t use any financial metrics. Even those using metrics often don’t take them seriously. “[A]lmost half … particularly the early-stage, IT, and smaller VCs, admit to often making gut investment decisions,” the report says.

They also don’t adjust decisions for risk factors — 78 percent either don’t adjust for risk or treat all risk the same. “VC firms … make decisions in a way that is inconsistent with predictions and recommendations of finance theory,” the report notes. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, they also don’t reflect much on their past hits and misses — only one in 10 VCs say they quantitatively analyze their past investment decisions and performance.

Nevertheless, having a metric that eliminates cognitive biases should be essential in any financial endeavor. Any VC not using financial metrics runs the risk of simply investing in people who look and sound like themselves or becoming anchored in anecdotal past experiences. Claims of strength through “pattern recognition,” can just as easily be weaknesses rooted in unconscious bias. And it’s an interesting disconnect, when after all, most VCs love to invest in data driven businesses.

So what financial decision criteria should VCs use? The Harvard study identifies the most popular metrics as Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC), used by 63% of VCs and Internal Rate of Return (IRR), used by 42%. However, neither metric is well suited to evaluating extreme uncertainty, a core challenge in venture.

At Ulu Ventures, we use probability weighted multiple on invested capital (PWMOIC). This metric allows us to explicitly characterize and compare uncertainty across investments. Many VCs will say they want a 10x multiple on their investments. We want a 10x multiple probability weighted, which is a whole different animal.

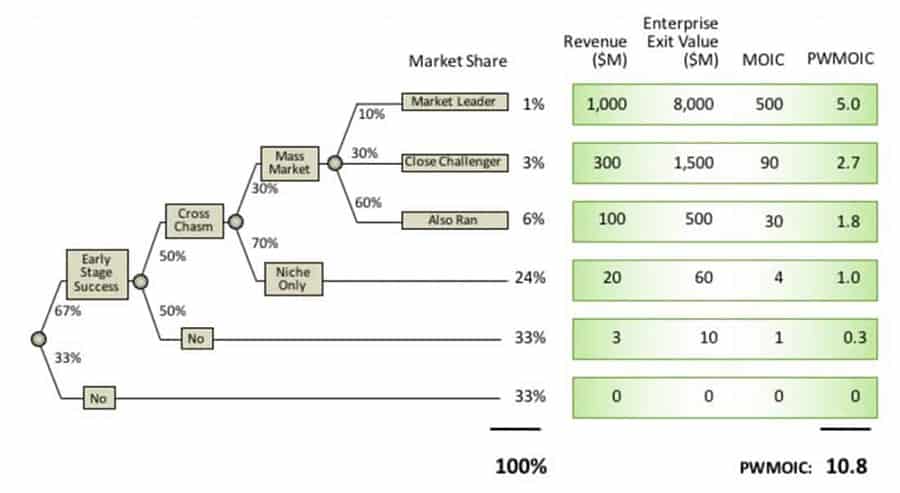

To calculate PWMOIC, we evaluate a decision tree for each investment, such as the one shown for a recent investment.

We explicitly model a wide variety of possible scenarios from becoming the Market Leader, the top branch, all the way to never achieving early stage success, the bottom branch. We then assess each scenario’s probability of occurrence based on data and expert judgment. In this case, the chance of becoming the Market Leader is only 1%, whereas the chance of never even achieving early stage success is 33%. Finally, we calculate the value of each scenario, represented by the numbers in the green boxes. For the Market Leader scenario, this startup will be generating $1 billion in revenue, the enterprise exit value will be $8 billion and Ulu’s MOIC will be 500. This sounds awesome; however, we discount the MOIC by its chance of occurring: 1% * 500 = 5.0 probability weighted multiple on invested capital for this scenario. The total PWMOIC for an investment is the sum of the PWMOICs for each scenario. If the bottom right number on the decision tree chart is above 10, then the company is in the investable range for Ulu.

This calculation is the same as an expected value calculation. However in venture, the expected outcome is often 0. Hence, we believe the term ‘probability weighted’ to be more clear.

When we started in venture nine years ago, we experimented with various metrics and personally saw the value of using PWMOIC. Of the 64 investments in our Fund I, we made 20 the traditional way and experienced a 50% failure rate to date. In these 20, we still did meaningful diligence such as reference calls, technology deep dives, etc. However, we miss-weighted important factors in making our final decision. With the other 44 investments, we followed a disciplined process to calculate PWMOIC and only 10% of these have failed thus far.

There is certainly a role for gut feel and expert judgment. However, with no true financial north, feelings and biases leave VCs open to systematic mistakes in other areas as well. For example, the conventional wisdom among Silicon Valley VCs is that you should always double down on your winners, investing early and then putting in more money in subsequent investment rounds. However, an analysis of the data reveals (insert link to reserve strategy article) that for most early stage venture firms working with a limited hoard of cash, investing more in the Seed and Series A rounds is a more effective way to boost returns.

At Ulu, every time we make an investment decision, whether an initial investment or a follow-on, we use the same process and the same PWMOIC criteria. We follow the advice of one of the world’s most successful investors, Berkshire Hathaway’s Charlie Munger, who says that, “Intelligent people make decisions based on opportunity costs — in other words, it’s your alternatives that matter.” We explicitly compare the PWMOIC of initial investments with the PWMOIC of follow-on investments. We’ve found initial investments to almost always score higher and so Ulu Ventures follows a strategy of aggressively investing upfront and reserving only a small amount for follow-ons.

So, why don’t more VCs use a more rigorous, analytic approach to making their investments? Some of it might be role models. Many famous VCs are known for their ‘midas touch,’ not their systematic approach to making good decisions. Some of it might be office politics, particularly in larger VC firms, where investments backed by senior partners often win support ahead of better ideas from junior partners. Without clear financial criteria for making investment decisions, influence can too easily trump logic.

A famous experiment by social psychologist Solomon Asch found that people often conform — agreeing with something that is clearly wrong — because they want to fit in with the group or because they believe the group is better informed than they are. This is just one of many ways in which VCs can fall victim to the herd, especially when a senior partner wants support for a bad bet or other top tier VCs are competing for a deal.

The venture industry recognizes the importance of good decision making in driving venture returns. The Harvard study revealed that 49% of VCs believe the ability to make good selection decisions is the most important driver of venture returns. This compares to only 23% who believe sourcing to be most important and 27% who believe value add is the most important. And yet, most VCs rely on their gut instead of data and metrics. Why?

Anyone who has seen the HBO sitcom Silicon Valley suspects there may be arrogance and hubris among VCs, many of whom think they are among the smartest people. For some, there may be a bit of truth in that sentiment. However, when you start from an intellectual position of believing you are so smart that you don’t need data and metrics to make financial decisions, you unnecessarily increase your risk of failure.